Bob M. on Oneida Ltd. quality

One thing about Oneida is our quality of our product was exceptional. There wasn't anyone that could

meet our quality standards. We were the top dogs.

Bob M. on Oneida Ltd. quality

One thing about Oneida is our quality of our product was exceptional. There wasn't anyone that could

meet our quality standards. We were the top dogs.

Dick T. on Increasing Competition from Imports

You know something? I can lay [Oneida’s collapse] to the feet of competition. And I think I saw it for the first time when I was on the Silversmiths Board. [I was] elected to it, which was a proud day for me, in 1988 I became one of the Silversmiths guys. About 6 or 7 years after this, Gary Monroe, we were at our regular meeting, and Gary had been there early. And the whole table was covered basically with tablecloths. Finished our regular Silversmiths meeting and he says, “Guys, take a look at this.” It was like a 120 piece set of stainless flatware, pretty good quality, with a price point that we couldn't come close to. I mean, the writing was on the wall. It just went overseas. Everyone started going overseas to have their stainless made, sending sometimes their own equipment over there, we were a little bit late to doing that. But it was just costs, it was so expensive. We tried lean manufacturing, and we weren’t even really 100% successful at that. So I think it’s a matter of the product we had, the competition, and it was being made much more cheaply in other places. And in the beginning, it was not a big deal because it wasn’t really high quality. But when they started getting to the quality, using 18/10 stainless, doing some nice finishing. And department stores saw it, do you want to pay $150 for Oneida, or $75 cost for this? It’s going to be significant, and I think it really comes down to that in the end. Could we have lasted longer? Could we have done it a different way? You hear that asked a lot. “It didn’t have to go the way it did. It could have been done better, and more humanely for everybody rather than just taking the cash that we had and paying big bucks for two operations.” We paid and got rid of the cash, so nobody wanted us anymore. But that’s it, it happened quick.

Laura H. on her father running the Toluca factory

In the plant, which was about an hour and fifteen minutes away, an hour and a half away, from their home in Mexico City, it was in Toluca. And the rapport [my dad] had with his Mexican workers that being out in the plant and being able to walk and talk and show and understand what they’re doing. And they all knew that [my] Dad was tough in terms of standards, but if you followed the rules and met the standards, life was good [laughter]. And he had a fly-tying bench in his office, in Toluca, and a lot of the workers during their lunch hours were invited to come in if they wanted to learn how to tie flies, and would sit with him at his fly-tying bench.

Bob M. on Oneida's Name Recognition

What was nice is that I’ve always felt very proud to be able to say I worked at Oneida because Oneida had a name. Oneida was the leader. When it came to tabletop, the industry itself, everybody knew about Oneida. Obviously, we had a brand recognition I think way up in the 90th percentile, which was actually a higher brand recognition than McDonalds.

Janet C. on Company Benefits

It [Oneida] was the major employer in Sherrill. At one time we worked three shifts 24/7, employed 3500 people. We had plants in Niagara Falls, Mexico, Ireland, and here. We had factory stores in almost all of the 50 states. It was a unique company in that we had our own credit union. We had our own insurance. Health insurance and car insurance were right there at the company. You never had to go anywhere else. You only had to go over to the factory, to the office, to do your car insurance [or] your health insurance. We had a medical department. We had nurses. We got flu shots, tetanus shots. We were well taken care of. Also, they did eyeglasses. You could get your eyes examined and get eyeglasses. You never had to go anywhere else for that either. The credit union was handy. Your paycheck could go right in. I always had loans all my life at the credit union for cars and whatnot. You got your paycheck, [and] it was already all taken care of. You didn’t have to worry about going and paying it.

Don on Valuing Employees at Oneida

I think the most important thing overall is you weren’t a number. You were a real person, the other people knew who you were, they cared about you. They wanted to know what your kids, your parents, where you went to church, whatever. And you better, as a manager, be doing the same thing for your people, which I always tried to do. For me, that’s what Oneida really was.

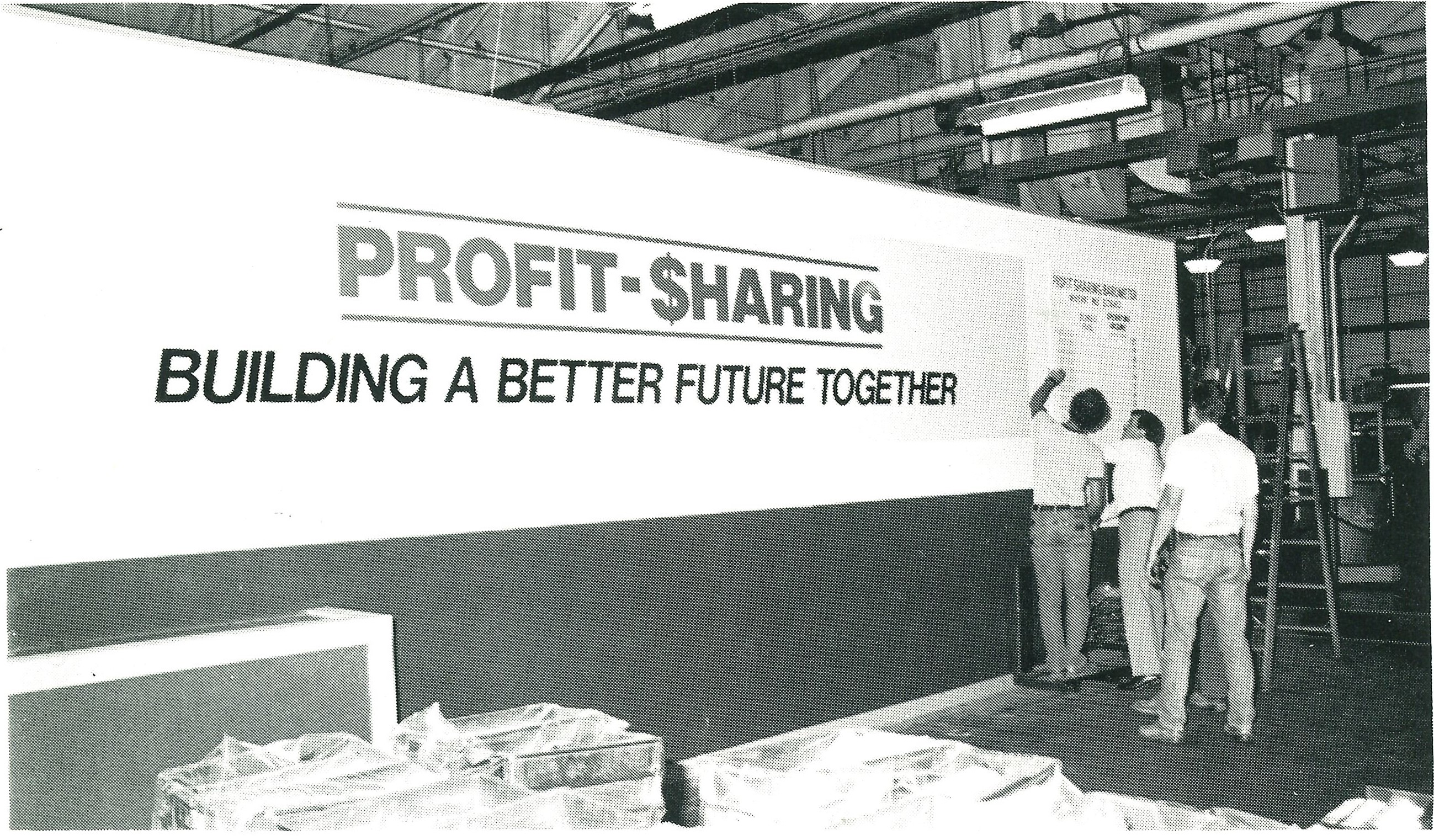

Tim C. on Oneida’s Commitment to Fair Wages

I always point out PB Noyes’s remark that their [Oneida’s] philosophy was “nobody rich, nobody poor.” They would pay less at the top to get more at the bottom. And of course they had profit sharing, which was nice. Again, that was, kind of enhanced the teamwork or camaraderie we talked about. If you had a good year, everybody benefited, you know. If you had a bad year, “Well, okay, no bonus for you.”

Paul M. on Lewis Point

It was quite a place down there. I think I said it was the most expensive piece of property on Oneida Lake. The most acreage of a point on Oneida Lake. There were 60 acres down there. It was quite a bit. It was just a fun spot. They’d have bands on the weekend, Friday night fish fries. Everybody looked forward to going to Lewis Point. They had softball leagues too, which were over at Robertson Park. Oneida donated that property to the city. It was 10 [or] 12 teams there most generally; every department had one or two teams. Out of the factory it would be silver buff, or black buff, or engineering. That would be their softball teams they’d have there. That lasted for quite a while. Doug and I would have to come up [and] line the fields, get it all set up for the leagues that night. That was all fenced in, it was a really nice setup over there that they had.

Don C. on Employee Treatment by Management

Everybody went by their first names. [CEO] Pete [Noyes] would come down, and most of the sales managers would come to us when they needed something for sales meetings. And someone would always come down afterwards and thank us for the work that we did. And [Oneida Ltd.] just was a good place to be.

Geoff N. on pay cuts for Oneida Ltd. executives

What happened in the bank scare, this short depression in 1921. My grandfather [P.B. Noyes] got up,

maybe in this room and walked around and said, "Okay, we're Executives, The Board of Directors.

We're all cutting ours [salary ] 50%. We're going to cut our salaries 50%. Everybody else: nope.

Everybody else won't take less. The guy that is buffing a spoon is going to take the least cut. Okay,

done." Then they decided after things got better in the '20s, they have an HCL, "High Cost of Living"

bonus right in there. Everybody got an HCL except the Executives. That was the socialism. My

grandfather kept saying that, "We're always going to run this thing for the employees."

Jim C. on meeting Pete Noyes, President of Oneida Ltd.

I have a great story about when I met [CEO] Pete Noyes. When I was 18 years old, he walked through

the factory and handed out cigars to the men for Christmas and chocolates to the ladies. And here I

am in the machine, 18 years old, and he went to hand me a cigar. And I said, "I want the chocolate." I

didn't get to see him again because I only worked summers. So 4 years after that, 4 years years down

the road, I'm in that same machine. I'm in the same machine. And it's Christmas time again. And he

walks up. Now, I haven't seen this guy in 4 years. He looks at me and goes, "You want the chocolate!"

And when he walked away, I had a new respect for what he remembered. Now, I don't know if I was

that easy to pick out, but he remembered that I didn't need a cigar. I was a runner. But he remembered

that night. I just stood up and said, "wow," that's what guy he was.

Pauline C. on Remnants of the Oneida Community

It was exciting to work on, to develop a line of consumer flatware that, for example, the packaging and all the marketing material, had to do with Oneida Community and how this is a historic institution, and that the emphasis on quality of material and being good to employees came out of the Oneida Community. So that was fun. That was unique in what I was doing. Because the different levels of flatware, for example, really did not change. There was, you know, the cheapest stuff and the most expensive stuff, and that stayed the same throughout the time I was there.

Jack S. on Dunc Robertson

I remember when I first started there. I could see this older gentleman, here I’m 18 years old, come walking up the aisle, stopping and talking. I knew he didn't work here. He stopped to talk to the guys on the wheel, wanting to know how things were going. Well, I checked him, it was [CEO] P.B. Noyes. He was retired now, but he still had a big interest in the company and the employees. And Dunc Robertson, he was general manager. He ran the place. They called him up one day and asked him to be over at the factory at 1 o’clock. Well jeez, Dunc figures right away, “they’re starting a union.” Well, they had taken up a collection and bought Dunc a brand new 1949 Ford. Jeez he was beside himself with tears.

Matt R. on Family Day

One of the other benefits was every few years they’d have what they call Family Day, all paid for by the company. You didn’t have to pay a penny. You’d go to Lewis Point, bring the kids, [and] all the rides are free. They would have clowns and all kinds of different events - three legged races and all these things for the kids. I mean I think the last one that we went to, I remember I think it cost the company, this is in the late 90s, I think it was $50,000 (approximately $96,000 in today’s dollars) they spent for one day for the employees. Just a great thing.

Janet C. on CEO Pete Noyes

I want to tell you my favorite and best story about [CEO] Pete Noyes. He will forever be in my heart, I can just cry just telling you about him now. He was a super-duper man. He would come up to you at your common everyday job, and he’d say, “Well hi young lady, how are you today?” and “How do you like your job here? How do you like it here?” And the person working next to me would say “who was that?” And I’d say, “Oh that was Pete Noyes, he’s just the CEO of the whole company.” And they’d go “Well wow, he just talks to you like you’re regular folk.” And I said “Yes, isn’t that wonderful?” Because he did treat everybody like they were regular folk. And I have a really soft spot for Pete.

Paul M. on Fire Safety and Security

They had a volunteer fire department. Oneida Ltd. bought, donated a lot of money to the fire departments [and] the police departments. We had our own security department, three shifts of it. And a lot of the firemen worked in the factory, so even though the factory was on fire, often the fire department got paid by Oneida because most of the fires were at Oneida. So they paid for the firemen in a roundabout way. They come to put their own fire out that they probably just started [laughter]. But they had their own security department too. There were three shifts of that. They had a lot of buildings to take care of. I think there was probably 20, 25 security guards out in three shifts to take care of. They took care of all their own insights, all their own codes.

John R. on Unions at Oneida

You know there’s quite a few times where an outside union would try and come in to get the workers to sign up as a union shop. And more times than not, they walked away saying “We can’t offer what the company already gives the employees, so it’s not worth [it] for the workers to become unionized.” So you know that [Oneida Ltd.] had a special interest for the workers, for the people.

Neal R. on the Oneida Community Golf Course

I mean the Oneida Community Golf Course was, I don’t say legendary, but it was just a place [that] was very tough to get on if you weren’t an employee. It was very hard to become a member if you were not an employee of the company. And it was phenomenal in condition. Executives in Oneida liked golf, so they didn’t hesitate to spend money making the golf course top notch.

Matt R. on the Size of Oneida's Factory

My grandfather worked for the company for a long time. And I remember as a kid going to Lewis Point out at the lake. So I knew a little bit about the company, but I’d never been in the facility. I came from a high-tech industry at the time, and initially I thought to myself, “Well these guys are making spoons and forks, I mean how hard can that be, you know? Geez, c'mon." We were making stealth technology and all that kind of stuff. So when I went through the facility, my jaw literally hit the floor. I’m a techie guy, and I [like] how things work. I said “You got to be kidding me, there’s no way that all of this stuff…” Because when you drive by the factory, you see the brick buildings in the front from the 1800s, and you think “Well geez, that’s not that big of a factory.” Well when you get in the back, and there’s a million square feet on 90 acres of land, and there’s 2000 people, and they’re making millions of spoons every week. Just the sheer size and number of people, and the activity level, was just unbelievable. I said, “There’s no way.” I said, “This is really cool.”

Bob M. on First Day of Work

My very first day, June 3rd, 1974. My first day at work, 10 o’clock I am told that everybody goes in for coffee in the cafeteria. So I went in with a group of guys from the advertising department, and they had a machine, a coffee machine. So I went up to the coffee machine, and I put in a quarter. Now the cafeteria has probably 30 [or] 40 people now in there, sitting around. And it’s pretty loud, everybody’s talking. You know, you had a 15-minute break. So I put my quarter in, and nothing happened. So I hit the return button, and nothing happened. This is my first day, so I’m pretty nervous. I think I’m 22 years old. And all the sudden, someone taps me on the shoulder, and I turn around. And there’s an older gentleman there, and he says, “What seems to be the problem, sonny?” I said, “Well, I put a quarter in, but nothing’s happening.” He says, “Step to the side.” So I stepped to the side, and this gentleman gave this machine a swift kick, literally kicked this machine. And the coffee cup comes down, and the coffee starts pouring. But of course, when somebody kicks a machine like that, the noise, everybody stopped. Now you have 30 [or] 40 people that are all looking up because this noise was just absolutely incredible. I’m redder than a beet. And I looked back, and this gentleman looked at me and he said, “Just like the horses, sometimes you’ve got to kick them to get them to run.” And I said “Okay,” and I said, “Well thank you very much sir.” And he says, “So what is your name?” I said, “I’m Bob,” and he says, “Well I’m Pete.” We shook hands, and I said, “Well Pete, very nice meeting you, and thank you so much for the help.” And he said, “Bob, anytime.” Anyways, I leave, I grab my cup of coffee. I go back to the table, and one of the guys I was with says “What the heck just happened?" And I told him that this gentleman helped me get my coffee, and he kicked the machine. He says, “Do you have any idea who that is?” And I said, “Well yea, I know who it is, it’s Pete.” He says, “Pete, that’s Pete Noyes, chairman of the board.” And I said, “Well he’s a really fine gentleman, he helped me out, and he’s a real nice guy.” From that day forward, every single time I saw Pete in the hallway, he always said, “Hi Bob, how you doing? You having any problems with that coffee?” And well, he was a wonderful man.

Janet C. on Sunset Lake

Of course, there was Sunset [Lake]. Sunset Lake was a manmade lake, which I understand they made on purpose as a water source for the knife plant and this Mansion House. Because this Mansion House, trust me, it’s a big old fire trap kind of a building, and they needed to be able to get water in a hurry if the sucker caught on fire. But Sunset also was a swimming hole for us kids when we were growing up. We didn’t have no fanky-danky pool with chlorine and lifeguards. We swam, and the fish nibbled us, and we learned how to swim. They gave lessons, [and] they bused us over. And Al Glover, he was the father of swimming lessons, he taught me how to do all the different strokes. But my brother, who was Al Glover’s buddy, classmate, whatever. They ran Sunset together. And my brother ran the concession stand, which was where you got your frozen milkshakes, and you got your little basket to put your clothes in while you went out to swim. And you got your Bazooka Bubblegum for a penny and your pack of gum for a nickel, which, you know, [was] them days. [They] are gone now.

Jim D. on the Archery Club

They took an interest in making sure that we were happy. They had a lot of clubs, too, that you could join. I got involved in the gymnasium and then also the archery club, which at one time had 60 members. And it was like playing golf. There was 42 targets in the woods at different distances, and you walked the trails from one target to another. And then in the wintertime, we’d shoot in the CAC gymnasium. [They would] roll out the nets and the backdrops and targets and stuff like that, and then we’d shoot in there.

Tim C. on Open Communication at Oneida

If you made a mistake, nobody gave you a hard time. They just helped you correct it and move on. If you had a question, you knew who to talk to. And somebody you could communicate with, you call “I got this problem,” [they reply] “Oh here’s what you do” or “hey you better call so and so because they handle this.” Okay, I mean you could get things… You get things done quickly and done the right way the first time. That’s what I think made the company so successful. I think that those kinds of relationships were the grease that kept the wheels going in the whole operation. Like I said, you got a problem here or question “who do I call?” Well, talk to your boss. “Oh, call so and so.” [You] call so and so, “Ahhh no, you’d be better off checking with…” You could have your problem solved within an hour. That was nice to be able to work like that. And, you’re right, nobody shut you down no matter how high up you had to go. Nobody said “no,” nobody said "don't bother me, call me back later.” Nobody complained to your boss, “why am I talking to him, he should be…” None of that.

Tim C. on Halloween at the Mansion House

Another time we needed to do something. We thought we’ll do something unique. It was around the Halloween time, so we decided we were going to have a haunted house. But it wasn't a haunted house, it was a haunted basement in the Mansion House. We actually went down in the basement, and we decorated it as a, I’m going to call it a haunted house. We decorated it all, and it was pretty amazing. We scared the living bejesus out of most of them, and they had a blast, and we set up a bar down there. Everybody had a great time.

Dave G. on Communications Day

Various chairmen of the company would hold, I think they call them Communications Day. Each month, they would go around to all the… I don't remember exactly how they divided it, but they would have various departments both in the administrative office and in the factory across town. They would go meet with groups of employees. They would set aside pretty much a whole day for it and meet with a series of employee groups one after another at the various locations. And it was pretty much an open Q&A session. They would start out with a brief report on the status of the company, any particular announcements they felt were needed to be made at that time, things that were going on. And then they would open it up for questions, and it was fair game. Employees could ask about anything they wanted to know about the company, and the chairman would reply. It was very open forum. Employees, they became used to those sessions, and they weren’t hesitant to ask a lot of questions that in other places people may have been too intimidated to ask about, but it was encouraged for them [at Oneida Ltd.]. Obviously, they would be respectful, but they were not afraid to ask questions either.

Al G. on Factory Tours

And another thing when I was chauffeuring, I enjoyed taking people on tour. People from all over the world would come in, and Oneida Ltd. automatically would take them on a tour. And sometimes I went on tour with them, and it was so much fun to see a supervisor of Oneida Ltd. take these people on tour, go up to a machine, and explain to them what this man or woman was doing as far as handling flatware, cleaning it, and all these different things they did. And all of a sudden, the worker, the man behind the machine or the woman behind the machine, they took over. And honest to God, Linda, it was so nice to see the pride that that person took in what they were doing. You know, it was so neat.

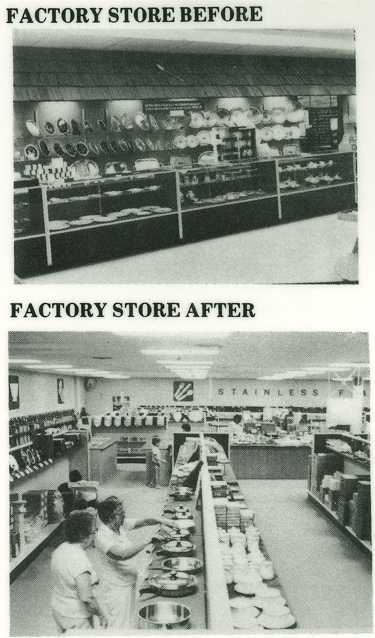

Dick T. on the Success of Factory Stores

Through the years, the concept [of factory stores] grew and grew - through the 80s and through the 90s. First million dollar stores we sat in Reeding in 1980. And then we had a million-dollar… month later on in 1988 or 1989. And then in 1997 the first million-dollar week [across all stores]. I was on the phone most of the day on Monday getting the numbers. You always got the numbers, but that day, I knew it was big. Because I already knew that we had over three days, over the big days Friday, Saturday, and Sunday we had done $555,556. I can remember, there were so many fives that I never forgot that. I said “You know, this is going to be it. You add those other days in, I think…” So I started calling the stores to get their numbers for the week, and sure enough, we did it. A million-dollar week, all cash, in the bank. That was the other thing that was great. Talk about cash cows, the factory stores were. I mean they could reach in on that Monday, and they’d pull in a million dollars.

Paul M. on Family Day

They [Oneida Ltd.] always had that stuff to take care of the employees because they didn’t want the union to come in. So, you know, they paid them well. You had a place to bring your family. They’d have a family weekend down there with all the rides and all the bands, and it’d be a Friday, Saturday, Sunday all set up. Saturday night was a big dinner night. All the families would come down. Kind of mix together everything there. And then when things shut down, they would have whatever was left over be the foreman's clam bake. Everyone in the factory that was foreman or management, they would come down, eat and drink, and play cards, have a good time down there.

Don C. on the Silver Niblick

They always had a big shindig at the CAC office, once every two or four years, I can't remember. They had a golf outing called the Silver Niblick. And that was always a lot of fun. Or they would bring in people who did our advertising for us for free. And that’s how we awarded them was we would wine and dine them, and put them up for the weekend. And then they would come and play golf. And it was kind of a big party. Lot of misbehaviors. There was an Oneida room that they created down [in the] cellar in this Mansion House. And it’s still there, where they entertain quite a few people. And they’d have clams and drinks out on the golf course and under a tent. And it was just a big party.

Don A. on working at the CAC

Then I was offered the choice of two jobs. One was Night Superintendent, and the other was the CAC

[Community Associated Clubs]. Probably the night superintendent would have given me more

opportunities as far as managing, but the CAC is something I really liked. So I chose what I liked. It

was a very interesting job. I loved it. Dealt with everybody. I was in charge of the Retirement Club. All

the different events were mine. Clubhouse, softball, Lewis Point, Family Days, the craft shows, the

bowling alley, you name it, anything that had to do with recreation. I loved the job. And basically, I was

there until I retired. We did our family days. I did the Kids' Fishing Derby and the Adult Fishing Derby.

Of course, many bowling leagues. We ran the golf leagues, not the golf course, but we did the

leagues. That was part of my duty. A Monday night league, a Tuesday night league, Wednesday

daytime league. We had a retirement league on Thursday. Thursday night were women's league, and

then we had couples' league on the weekend. We had maybe up to almost 10 leagues. It was busy.

Bowling was in the bowling season. Summer, we had up to 16 team softball leagues that we ran over

in the old Robertson Park by the retirement home. We had those leagues. We ran those for several

years. We actually had a league for the night shift that would run during the day. Anything that people

were interested in, we tried to follow. We tried to make it happen for them.

Matt R. on designing and building machines in the factory

When I was running the factory, I think we had 22 mechanical engineers, 2 electrical engineers, 8

chemical engineers, because we did a lot of silver plating, probably 50,000 pieces a day, and all kinds

of technical people, tooling people, and technicians. Almost all of the equipment was designed on

site. We didn't buy equipment that said, "Okay, we need something to stamp our flatware," we

designed it and built it ourselves. Actually, some of the equipment was, the coining press as an

example, the one that stamps the handle in the bowl. For about 10 to 15 years, because it was

developed here and it was top secret, they had competitors, they kept all of that equipment behind

closed doors. They tried to keep people from seeing it. Certain parts of the process was reserved for

top secret clearance only.

Al G. on the family atmosphere of Sherrill

And then people used to ask me, "What's Oneida [Limited] like?" And I chauffeured. I said, "If there's a

death in the family, if there's a marriage, anything that the community would be involved in or know

about, you had people there to help you. You had gifts, you had food, you had money, you had

anything you wanted because it was one family town." I feel so fortunate to be able to live in Sherrill,

be a part of Sherrill, and do the things I did in Sherrill, and you work at a company like a Oneida. I had

my ups and downs, but I had more really ups.

Janet C. on Oneida's teaspoon promotion

Back in the day, Oneida Limited advertised in brides magazines for brides to send in a quarter--later, it

was 50 cents--to get a sample teaspoon, a real-life teaspoon, so they could decide what their pattern

was going to be when they got married. And all day long, we processed hundreds and hundreds and

hundreds of envelopes with quarters and dollars and letters. We preserved their names and sent the

spoons back to them. And we kept their addresses. I would imagine that Oneida Limited sold those

mailing lists to others. We had to photocopy those coupons for that reason. I don't remember how

long I was there. Eventually, they did away with the coupon redemption, but you would be amazed

how people send money through the mail. They stuck it in gum, they wrapped it in a Band-Aid. I can't

think of everything, but it was a blast. And people ordered 1 teaspoon or they could get all of the

samples for $3 or $4. We sent them all to them. It went over to General Mills over in the factory, and

that's what those ladies did, was just stuff those spoons in an envelope and send them. I'm sure that

it was a boon to the company because I'm sure they got a lot of business from these brides, they

ended up ordering a whole set of whatever their favorite pattern was.

Matt R. on valuing workers

The legacy that I felt, and it was more of a cultural thing, when I started in 1991, there might have

been people that were working since the '50s, and those people learned from people that were there

in the '20s and '30s, is nobody was more important than anyone else. In fact, it was actually the

opposite. Most of the management in the factory, when you were working in the factory and you were

producing good product and you did a really good job, you made really good money. Oneida paid their

hourly workers actually better than the first-line supervision. We have in our company today, Sherrill

Manufacturing, one of our Director of Operations, Jose Alvarez, he told me the story that when he was

offered a job in supervision, we're talking back in the early '80s, that he came home and told his wife,

"I've got really good news, I got good news and bad news. The good news is I've been tapped to be a

supervisor, the bad news is I've got to take a $3 an hour pay cut to do it." So they valued the people

that did the work very highly. If you look at the CEO's salary versus the wages in the factory, the

multiple was not like it was in other companies. They were fairly well paid, but nothing like they were

in other corporations in the rest of the United States. I think that's a vestige of the [original Oneida]

Community where everybody's important.

Paula N. on multiple generations working for the company

And I just got to say that my parents, my husband's parents, my husband and myself all worked at

Oneida, and we're proud to do it. You would talk to somebody in a store or somewhere, and they'd say,

"Well, where do you work?" "Oh, I work at Oneida Limited." And then they would say, "Oh, it's great to

work there. The people are good to you. There's many benefits to a lot of jobs. You would love it." So

then it would make you want to go and check it out and be a part of this family, especially when Pete

Noyes and Bill Matthews were the CEOs, they treated you like you're family.

Tim C. on the local doctor

Old doctor Prowda was the was the doctor over in Sherrill. And, Oneida Limited had what they called the "Jitney" which would take things back and forth between the sales office and the factory. You know, paperwork or whatever. You know, a sample that somebody wanted to look at. Another part of the Jitney's job, the driver, was to pick up retirees and take them to their doctor's appointments. If they couldn't [or] didn't have a way to get there, [or] could no longer drive. Somebody had to go and have an appointment with Doctor Prowda, you know, be able to be a retired employee and, they couldn't drive anymore or they couldn't walk to the place. If they needed a ride, they would get them a ride. And, of course, the Oneida Community's visiting nurses. She would go around, make sure everybody was whatever, change their bandages, getting their insulin shots, if they needed a walker or crutches or a hospital bed. This was taken care of by the corporation.

Don A. on closing the factory

One of the worst days of my career there was the final day when they told the Factory, and this was

right in the middle of the day, they told the Factory, "Shut down, everybody go home." And I had to go

through the factory to make sure everybody was gone, me and myself and a couple of my men. And

to see a coffee cup sitting there half full, maybe a portable radio still going, it was like a ghost town. It

was probably the saddest day of my life there to see where people had to just get up and go. One of

the other things that I hated about doing at the end was when people got let go, for instance, the

Sales Office, they were letting a bunch go. I had to go sit in the cafeteria with one of my men on call in

case they needed help. These were people that were my friends, and I saw people coming out crying.

It was sad. Not a fun part of the job.

Janet C. on the end of Oneida Ltd.

I remember it was right after Labor Day when they announced that we were going to be done. I don't

remember the time frame, but I sat on my bench in Brocade and I cried, real tears. It was so sad to

think that we were all going to be out of a job after so many years and so much blood, sweat, and

tears that we gave them. There was a minor reprieve for us for us Brocaders. They came on the PA

and said that when Sherrill Manufacturing bought, they were going to keep the warehouse, and

Brocade was part of the warehouse. And I was in Brocade, so I thought, I got a reprieve. I'm still going

to be working for Oneida. And I used to go to the P&C [grocery store] at my other job, and I used to

see all my friends that were going to lose their job and feel real bad for them because they were going

to [lose their jobs].... And I was going to get to stay. And then a couple of weeks later, they came on

the PA again and said, "Brocade's going too." And so all of a sudden, I was going to lose my job, too.

We came to work, and we did what we had to do, and we were very sad. And they got rid of us a few

at a time. To us, high service got to stay the longest. And I can remember the last day. We stayed. We

worked until the end of the shift at 3:30, pushing out as much silverware as we could onto the floor to

get shipped. When we punched out for the last time and we drove out the gate, I'm thinking, "Wow,

when I come back, I'm not coming back. I'm not punching in. I don't have a job." And it was like, except

for losing my parents and my favorite horse, it was the most traumatic thing that ever happened to

me. I had 32 years in, and where am I going? I had I had no skills except for horses. I went to high

school and took all of the college entrance stuff. I didn't have any skills [such] as secretarial. I'd been

injured in a horse accident, so now I walk with a limp and I had gray hair. Who the heck is going to hire

me? It was real hard surviving after that.

And the signs coming in and out of Sherrill with the teapot said, "Welcome to the Silver City" were no

more. And it's, "Welcome to Sherrill" now. But the teapot's gone....We're not the Silver City anymore.

Matt R. on founding Sherrill Manufacturing

So that's when I came up with this cockamamie scheme to buy the factory, and I called Greg Owens,

who I met in Mexico, by the way. We were neighbors down in Toluca [Mexico]. Yeah, we were

neighbors. We used to play basketball together and tennis, and we'd go on trips and barbecues and

watch football because all the expats down in Mexico, football to them was soccer. American football

is what we would watch. So I called Greg up one day, and I knew that he was working for some steel

business, and he was doing okay, but bouncing around. And I said, "Greg, just hear me out." And I

went through a list of things that make this factory competitive and some of the legacy things that

were an issue. And I said, "Why don't we just start with a blank sheet of paper? You've got a little sales

and marketing experience. I got a little operations experience. We both have some experience." He did

work for Oneida for a little while in the factory in Mexico. And that's when we came up with the idea to

create Sherrill Manufacturing. And it's been 16 years. Now, I think the only people that can screw it up

is us.

We have a good business model. We're an Internet company. We try to treat our employees the same

way that Oneida treated their employees in the heyday. I know everyone in the factory by name. I talk

to them all the time. "And how are the kids doing? And your mom's sick. What's going on?" We live in

the community in which everyone else we work with lives in. And I think, "knock on wood," every time I

say that I think we figured it out. Hopefully, we're never going to be what Oneida Limited used to be. I

don't think you're going to see 2,500 people making flatware in Sherrill. But every day when I come to

work, I think of the tens of thousands of people, the many thousands of people that walk through the

same doors I walk through on a daily basis and gave me the opportunity, kept the factory around long

enough that we could keep it going.